Why Family Health History Matters: Baby Receives More Than just Daddy’s Nose!

November 1, 2021

Genetic health condition

You may have already noticed at your annual appointments, as well as visits with specialists such as your Ob-Gyn physician during pregnancy, that you are asked to report your family members’ health information. This often includes cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and known genetic conditions. All healthcare providers have some training in recognizing patterns of disease in a family that may suggest a genetic basis.

Each cell in our body contains an entire set of our genetic information, like a library. Our genes are the individual instructions our body uses to grow and repair tissues, including your baby’s beautiful eyes and nose! Our cells also need our genes to perform all daily functions from digestion to exercise to focusing your eyes on this text, and your brain interpreting and remembering the meaning of what you just read. Our body has two copies of each gene: one received through our father’s sperm and the second received through our mother’s egg. Genetic information passing from one generation to the next is called heredity, a child usually inherits half of their father’s genes and half of their mother’s genes (one from each parental gene pair).

Some genes are so important, that if one of the two copies of a gene pair is not functioning correctly, there is disease or a health condition. When one abnormal copy of a gene is enough to cause disease, that is considered a dominant genetic condition. When someone has a dominant genetic condition, there is a 50/50 chance whether they will pass on the abnormal or normal gene copy to each child. If a child receives the abnormal copy of a dominant gene, they will also usually develop the condition. A few examples of dominant genetic conditions you may have heard of:

- Achondroplasia (a form of dwarfism affecting the skeleton but not cognition.

- Marfan syndrome (connective tissue condition affecting heart, joints, and unusually tall height)

- Huntington disease (a fatal condition of progression brain degeneration)

Other genetic conditions only occur when an individual receives one abnormal gene from both parents resulting in a two abnormal genes for the same gene pair. If a disease occurs only when both genes are not functioning correctly, it is considered a recessive genetic condition. Recessive conditions can be “carried” by an individual when they have one normal gene and one abnormal gene but do not experience or develop symptoms. The normal gene copy has enough function to make up for the abnormal gene copy not doing its job. Some common examples of recessive conditions you may have heard of:

- Sickle Cell Anemia (a blood condition that causes pain events and anemia)

- Cystic fibrosis (progressive condition that causes decreased lung function and digestive issues)

A carrier of a recessive condition has a 50/50 chance of passing the abnormal or normal copy of the gene on to each pregnancy. If two carriers for the same recessive condition have a family together, each pregnancy has a 1 out of 4 (25%) chance of receiving the abnormal gene from both parents at the same time resulting in the child being affected by the recessive condition. There is also a 3 out of 4 (75%) chance the pregnancy will receive at least one normal gene copy, resulting in the child not being affected by the condition. This is why carriers of recessive genetic conditions often do not have a family history of the condition! If you would like more information about whether you carry certain recessive genetic conditions, please ask your Ob-Gyn provider for more information or ask to speak with a genetic counselor.

Most common diseases, such as diabetes or cancer, can have both genetic and environmental factors that make an individual more likely to develop the disease, rather than causing the disease directly due to a single abnormal dominant gene or abnormal recessive pair of genes. These are called multifactorial conditions and may not have genetic screening or testing available. Some patterns of family health conditions may be a red flag that there could be a stronger genetic basis for a certain familial health condition. Other genetic conditions may be caused by structural differences to genetic information affecting one or multiple genes or from missing or extra pieces of genetic information.

Accurate family health information helps your provider evaluate you and your pregnancy’s potential genetic risks. This information may guide recommendations for health evaluations and/or genetic screening and testing for you or your pregnancy. Since guidelines are constantly updated based on new research, your healthcare providers may discuss new recommendations at future visits.

Do I need to know the health of all of my family members?

Different general practice and specialist providers may want to know about the health of different relatives. Prenatal genetic counselors typically gather information on the following family members to a pregnancy:

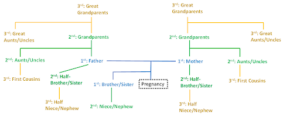

First degree relatives (in blue below): biological parents and full siblings of the pregnancy

Second degree relatives (in green below): Half-siblings to pregnancy (share one parent with pregnancy), aunt/uncle to pregnancy, grandparents to pregnancy, and nieces/nephews to pregnancy

Third degree relatives (in yellow below): first-cousins to pregnancy (children of parents’ brothers or sisters), great-grandparents to pregnancy (grandparents of mother and father), great aunts/uncles to pregnancy (aunts and uncles of mother and father), and half nieces/nephews to pregnancy

Non-traditional family members

Certain important members of your family may not be related by blood. Including close family members who are not related by blood may confuse a conversation about risk for genetic conditions. Step-parents and step-siblings are part of your family, but their health and diagnoses do not need reported during a genetics intake. If “Auntie” is your mom’s best friend and not your mother‘s biological sister, she is also important to your social support network and family- but her health conditions would potentially confuse a genetics family history intake and should not be shared with a genetics provider. We all have a chosen (unrelated) family in addition to our biological family, but your healthcare providers appreciate accurate relationship terms according to biology rather than the unrelated family we hold dear.

Not everyone knows their family health history for many reasons: they moved away or a parent moved away, they were adopted, or their family chooses not to share health history because some consider it to be embarrassing or otherwise taboo in their culture. Please honestly inform your healthcare providers when you have limited health knowledge about your family instead of assuming your members are healthy.

Some families have biological but “non-traditional” structures with aunts/uncles or grandparents adopting or raising another family member’s child(ren). While it may feel impersonal, please also use the biological relationship to describe these family members rather than your family name for them. Your healthcare providers do not mean any disrespect to your relationships, but genetic health risks depend on how a family member is related as well as their health conditions.

For example: please describe your aunt who raised or adopted you as “Aunt (her name)” rather than “Mom”. If using their biological relationship is out of habit and hard to do- clearly describe how the family member is related first and give their first name, then during the rest of the conversation simply use their name.

Health information on your close family members help your genetics provider estimate any risks more accurately you and your baby!

What health conditions should I report?

Pregnancies or children with a diagnosis

Any pregnancy, newborn, or child with a health condition or birth defect (e.g. cleft palate, heart murmur, multiple light or dark birth marks, extra or fused fingers or toes). Which body parts were affected and if the condition was present at birth and/or progressed (got worse) over time is helpful information. Please also let your providers know about children that passed away in utero, infancy, or childhood and any known physical or developmental differences those children had.

Adult-onset conditions

Any family members’ health condition that was given a name/diagnosis or that impacted their daily life should be described in your family health history intake. Age and cause of death can also be important information. Both named and unnamed conditions may be used by your healthcare provider to estimate your risk, or your pregnancy’s risk, for the same condition depending on that provider’s specialty and if the health condition is typically genetic in origin. If your primary care provider or a specialist thinks you or your pregnancy may be at risk for certain health conditions based on family history, whether typically genetic in origin or not, they may refer you to a specialist.

Onset of a health condition after a physically traumatic event: e.g. seizures after a sports accident or car crash; while unfortunate, do not usually have a genetic component. However, please still inform your healthcare providers about these changes in your family members’ health for a complete history.

Ethnicity/Ancestry

Ethnicity and ancestry are not medical conditions, but knowing where your ancestors came from can influence your risk for genetic conditions that more be more common in certain ethnic backgrounds. If you know whether you and your partner, or your parents or grandparents, shared a common ancestor, please also inform your healthcare providers as having ancestors from the same family increases the risk for recessive conditions.

Thank you for reading!

We hope you found this background on why family health history is important useful! Your providers appreciate your patience when we ask for this information, even if you have already provided it to us. Sometimes follow-up questions to your initial answers help clarify potential concerns or we are reorganizing the information to best look for patterns.

If you realized you do not know much of your family’s health history while reading this, the upcoming Fall and Winter holiday gatherings/video chats may be a great time to ask your family members for health updates!